Writing for robots – How to optimise your writing for LLMs

Who do you think reads most of your technical writing? Customers? Potential customers?

If your work is public and not behind a log-in, I hate to disappoint you, but your most frequent reader probably isn’t human. And this is nothing new. Since website crawlers began venturing out onto the internet to compile websites for people to find the information they need, services running on machines have been reading our work, casting a silent lack of judgment.

And now comes a new wave of machines guzzling our content to feed and train large language models (LLMs).

Whatever you think of the old and new wave of machines consuming our content, unless you disallow them, it’s hard to stop them. However, the good news is that writing and maintaining good content for humans also produces good content for robots! Yay?

In this post, based on a recent presentation I will record a video of soon, I recap some good writing advice. Much of which you hopefully already know, but it’s always worth revisiting and looking at why it helps machines, too.

Before I begin, a disclaimer.

I wrote this post mostly for people who write technical documentation and blog posts. However, much of the advice is useful for anyone writing online.

Stop the bots!

It’s a good idea to recap what benefits you might receive from allowing the robots to trawl your content.

Similar to how allowing search engines access to your content helps people find what they are looking for without you needing to do much work, allowing LLM training scrapers access to your content also benefits you.

I think we can all agree that we have never found an ideal way to help people navigate documentation and find what they need. We try tweaking navigation, creating meaningful headings, and adding search. Really, what most people actually want is a giant Google-style search box or someone to ask a question and give them an answer to their specific question.

Docs bot

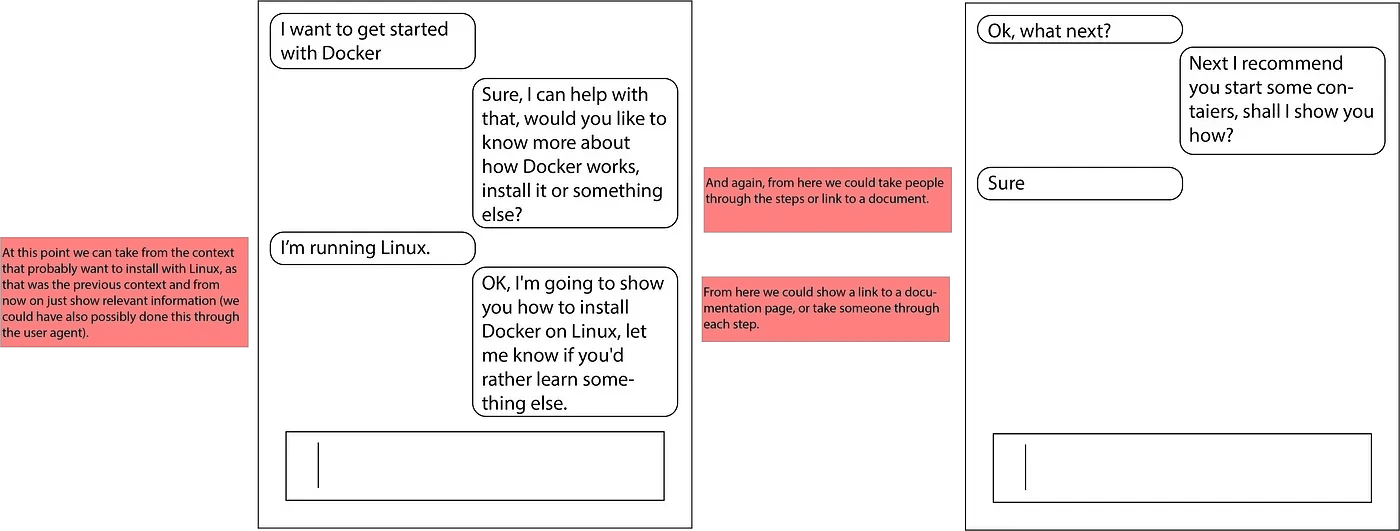

Several years ago, at a Write the Docs event during the last wave of generally terrible chatbots, I proposed a kind of “docs bot” that could provide you with information based on your questions. It could maintain context and continue answering questions based on what it has learned from you so far. At the time, it seemed like a crazy idea. But now, this seems like table stakes for any chatbot.

Well, the new wave of AI tools, especially those with chat interfaces, do just that. And it’s an increasingly popular option for many people.

Good structure

Good structure always helped web page scrapers identify the context of content and how different areas of the page relate to each other.

The same mostly applies to feeding an LLM. If a machine understands the content and how it relates to the content around it, it can provide better responses. I often refer to the NextJS documentation to highlight many best practices. Take a look at this page for a good example of a good structure. Why? Because it uses plenty of page elements to break up the content.

Let’s recap some of these (you should be doing these already).

Headings

Any web page, in fact, most pages in any format, begin with a title or heading. Regarding HTML, this should be an

, or heading level 1 for however your tool of choice represents headings.Every page should have only one h1, but unfortunately, many tools and people break this rule to the page’s detriment. Typically, right after an h1 is some opening text, and then every following sub-heading should be an h2. Then, every sub-heading is underneath an h2, an h3, etc. Most browsers comfortably handle everything down to an h5, but theoretically, you could keep going down the levels. However, if you have that many sub-headings, your content probably needs reorganising.

Headings should be active, gerund, and “-ing” style text describing what the reader learns and accomplishes from reading the section. This may become less relevant as you get further down the sub-heading tree but it should apply to at least heading levels 1–3. Descriptive headings have always been important before LLMs, but they are even more useful in this case, as they often represent the direct answers to people’s questions. For example, “How do I install this software?”

A related heading is “Installing this software”, which now means the tool using the LLM knows that the content directly beneath the heading is relevant to the question.

Meaningful links

The “H” and the “T” in HTML and HTTP stand for “hypertext” or, to be more precise in this context, “hyperlinks,” a somewhat ageing term for what we now call “links.” Why they’re called this requires a delve into history, which I am always a fan of but won’t do right now. Ultimately, the internet and its web pages are built on interconnected links.

Although the intentions, mechanics, and purposes of links have changed over the years, they are still a fundamental component of how the Internet works. We still use them extensively, and they also provide LLMs with sources of related content when answering questions.

Despite how essential they are to how the internet works, we generally implement them in sub-par ways.

I can’t remember where I heard this, but someone described to me that the standard way most people populate link text with words such as “click here, “here”, or “link” is equivalent to walking around a shopping district and every shop calling itself “shop”. You already know what it is. Telling you that again and again is completely unhelpful. In the case of links, there’s another machine consumer to consider: screen readers. Used by people with lower vision, these read the screen’s contents to the user, describing page elements and what they contain. So imagine hearing “link link, link click” over and over again the next time you think about link text.

Link text should be as descriptive as page titles and menu entries. Aim for link text that’s 3 to 5 words long and describes what the reader gets from clicking the link. For example

- “How to Install a Prerequisite”

- “The full list of configuration options”

This helps human readers, machine readers, and LLMs understand the context of resources content links to.

Alt tags

Images are wonderful ways to break up text and visually explain a concept. However, at this moment, most text-scraping LLMs don’t really understand what an image shows, and even if they do, they aren’t so accurate at describing them constructively.

A picture may speak a thousand words, but not if someone can’t see it. Any image you add needs a way for someone visually impaired to access the content, too. These users often use screen reading applications to help them navigate applications and websites.

At a minimum, you need to add an alt attribute to the image that tells a screen reader what to read in place of that image. Technical documentation can be poor regarding alt attributes as many of the tools documentarians use don’t prompt you to add them or give much advice on a good value. We also tend not to give much thought to what we add to alt attributes, often entering minimal text or, at best, text that describes what the image is; for example, “Screenshot of settings.” There are different schools of thought on what you should use for alt tags, but the best answer I heard was that an alt attribute should describe what the image describes. So, in essence, an alt attribute should tell someone who can’t see it what you wanted to communicate with the image in the first place.

For example, instead of “screenshot of settings,” use something like, “The screenshot shows how to change the text size using the value in settings.

Describe other elements

If you want to take accessibility a step further, remember my point about images and text complimenting each other. An image added with little context in the text around it may give enough information to someone who can see it, but with no context around an image, even good alt attribute text gives little help to someone who can’t see the image.

The same applies to all other non-textual images. If you add a table, describe what the table shows. If you add a code block, again, describe what it shows. If you add a video, ideally also provide a transcript, but at the very least, you guessed it, describe what it contains.

This means that when an LLM encounters media, it can’t fully understand (yet), but it at least understands what the item is supposed to show and could possibly suggest where you might find the element if you’re interested.

Large Language Language

I won’t go into too much detail here about writing good technical copy. If you’re reading this, I assume you already have a rough idea of how to do that, and if not, well, there’s a lot of content out there on the topic. Plug, I even have a book you can read… 😬

But in short, many of the same rules apply to writing for robots that apply to writing for humans.

Keep things clear and concise. Set aside assumptions. Use good grammar. Test that what you’ve written technically works. And so on.

Maybe one point to pay extra attention to is expanding and explaining custom terminology. Just because you and (hopefully) your users understand your own custom industry or project language doesn’t mean an LLM will do.

Feed the machine

Optimising technical copy for LLMs is, much like the LLM space more broadly, in an active state of flux. There’s a lot more detail this article could have gone into, and best practices will change. However, I hope the advice and ideas here at least get you started, and any of you who made it this far have already realised that, for the most part, anything good for humans is also good for robots. For now…

Support Me on Ko-fi

Support Me on Ko-fi